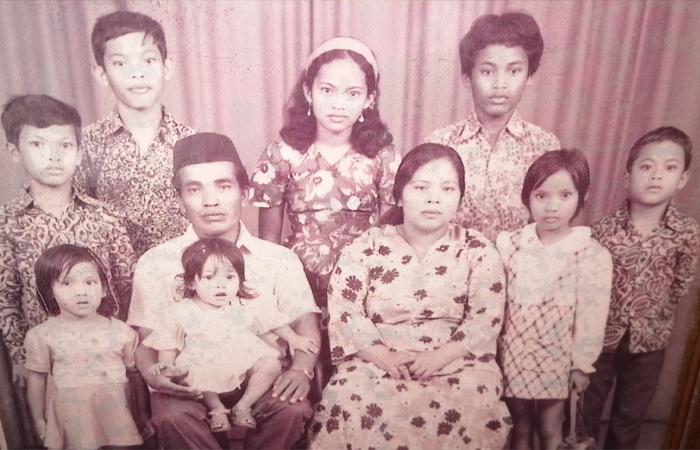

Kamar Ismail

The Christmas Island of today is almost unrecognisable from what it was like in the 1960s of Kamar Ismail’s youth and in many ways it’s for the better.

When the 54-year-old was born on the Island, it had only become an Australian territory less than a decade earlier and the Malay, Chinese and European cultures were still figuring out how to coexist.

Kamar recalls that his generation was the first to mingle freely with the other cultures on the Island.

“I’d mix around with Chinese, Malay, European and everybody like that,” he says.

“I didn’t feel the racial tension between the white or the black or things like that – but maybe my parents did.”

Evidence of racial division still existed at the time though, and being of Malay descent, Kamar experienced it first-hand, but he insists he wasn’t particularly bothered by it.

“They’ve got a swimming pool for the whites and a swimming pool for the Asians,” he says.

“Sometimes we’d jump into the whites swimming pool and some of the white people don’t give a damn.

“That’s how we lived in the 1970s but people were still happy.”

However, Kamar also witnessed the progress and Christmas Island is now a beacon of inclusiveness and cultural diversity.

“Christmas Island is very open to anybody really,” he says.

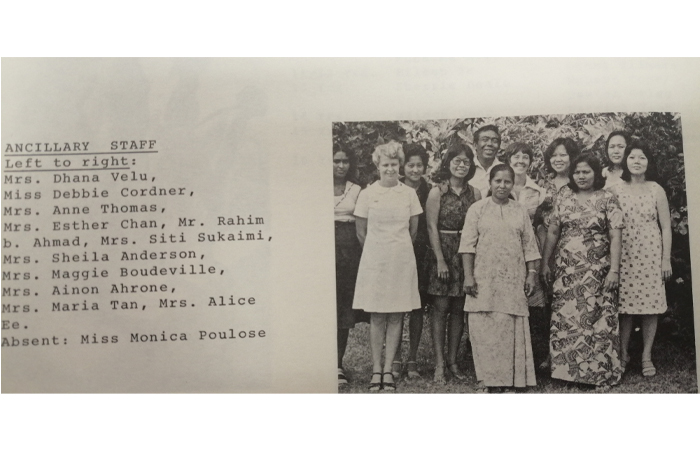

Education on the Island is another area that has seen vast improvements over the course of Kamar’s life.

When he was at school, classes were still segregated until the fourth grade and Kamar describes the education back then as only “very, very strict”.

The father of two is much more enthusiastic about the state of education on the Island when his children, one now a speech pathologist and the other studying to be a nurse, were schooled there.

“The government put a lot of money into the school, and most of the kids turned out good,” he says.

“Not only my kids – there’s other kids that are becoming doctors and becoming lawyers, everything.”

Central to many of these changes has been the Island’s phosphate mine – which has undergone a startling transformation of its own.

The presence of valuable phosphate deposits on the Island were the main driver behind the initial settlement and the mine has remained the major economic driver since it made its first major shipment in 1900.

In 1949, the Australian and New Zealand governments purchased the mine and continued to manage it until the effects of drought and low phosphate prices led the mine’s closure in December 1987.

Without the mine, there wasn’t enough work to keep lifelong residents on the Island.

“People were struggling, ships were coming very late and food was coming very late,” he recalls.

The Australian Government implemented a scheme that required people to leave the Island to obtain a resettlement benefit and Kamar was among the many long-time residents of Christmas Island who took the deal.

Kamar says he was motivated by a desire to see the world so he moved to Perth.

“I was in my 20s then, so I just wanted to go out explore other places,” he says.

“I thought I’ll just go down there and see how it is, if it’s not good I’ll come back.”

Those who remained fought to re-open the mine and that effort ultimately paid off when the union workers were able to gain a mining lease from the Australian Government.

The mine started operating again in 1990 under the name Phosphate Resources and it triggered renewed prosperity for the Island.

“It made a lot of us come back here and it was affordable to find homes and put kids to school, that’s including me,” he says.

“The mine is like a big tree that holds many people, its roots are out, and people will jump on to that root and start to get things going.”

Kamar returned to the Island in 1996 and worked odd jobs before landing a store manager role with the mine, where he continues to work to this day.

However, the Island’s dependence on the mine presents problems of its own.

For all that the Island has improved from Kamar’s youth, the notable exception is the prospect of a permanent end to mining that current residents are facing.

“The mine is very, very important to the economy,” he says.

“But the mine can’t go forever.”

The mine’s current lease is set to end in 2034, but Kamar doesn’t think an extension would keep it in operation too far beyond that.

“There’s not much left if we keep on mining,” he says.

Although mining remains the central economic hub for the Island, other industries are present there.

With the Island on the brink of new wave of change, one of these industries will need to fill the gap.

The tourism industry is a promising area with the Island abounding in natural bounties and a unique culture.

But Kamar says the existing tourism offerings aren’t successful enough to support the economy in the absence of the mine.

“People will come here and pay $600 to stay in a room for a night,” he says.

“It’s for luxury people who can go diving, things like that.

“To get a day-to-day person like a backpacker to stay here, I don’t think you can do it.”

A new resort is being proposed and is expected to be built in a decade or so, which should cater to a bigger market, but Kamar has doubts the Island’s current infrastructure could handle a substantial increase in visitors.

“How many tourists can you put on the Island in a day?” he wonders.

“You can’t put 500 people here, there’s not enough facilities to go around.

“We don’t have enough shops, we don’t have enough restaurants.”

For Kamar, a possible solution which could unlock tourism and other industries is to increase the population from where it currently sits at around 1,600 people.

“You need to build the population,” he said.

“If the government let you build the population then this place will be different.”

However, Kamar recognises that approach is not without its own drawbacks and it must be carefully considered.

“By increasing the population there are positives and negatives that you need to study,” he says.

“If you increase the population, is there enough drinking water? Where do you want to throw the rubbish? Is the population capable of reaching 10,000 people?

“We have to look at all aspects.”

The mine has been active in engaging with the community to chart a course beyond mining, but Kamar believes it will all depend on the Australian Government’s vision for the community’s future.

“If the government says, look, we’re not going to build anything, then what economy can you have?” he says.

“It goes back to the government and how they want to look at this, what they really want this place to be.”

Kamar has lived on the Island for most of his life and his love for his home hasn’t diminished.

“It’s beautiful,” he says.

“The ocean is close by if you want to go fishing and if you want to go for a boat ride you wouldn’t have to pay fees.”

But he accepts his time on the Island could end along with mining.

“I’m 54, I’m on the ending block,” he says.

“I’m ready to be more, I’m ready to move on.”

His concern is for the younger generation who have set down roots here.

“There are people who’ve really committed themselves, who bought a home here and they’re just thinking this mine will go on forever and it will not,” he says.

“It’s going to be a tough ride I think in a few years.”

Kamar believes the solution can’t come from his generation, it will be up to the new generation of Christmas Islanders to chart their own course while the mine is still in operation.

“The people that want to live here, they definitely got to open up themselves and speak to groups of people and try to work it out,” he says.

“What do they really want?”

Nothing can stop the change that is coming for Christmas Island, but how the government and the younger generation answer that question will be the deciding factor in whether it’s a change for the better.