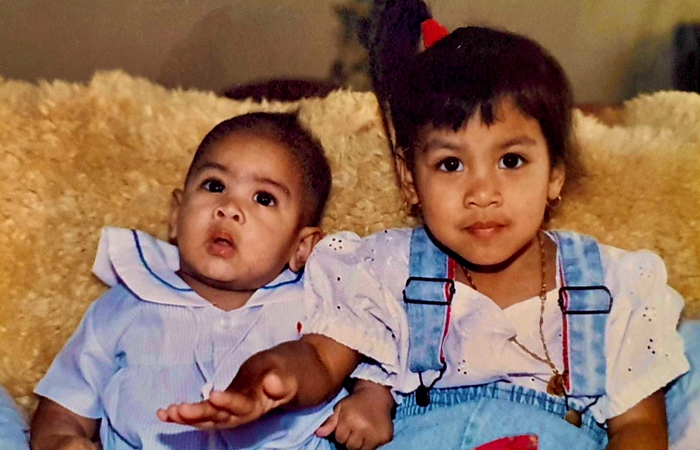

Khaliesha & Khairin Amin

With no people indigenous to Christmas Island, every human living there is either a migrant or descended from one.

But there are still families who have lived on the Island for generations and have an extensive, treasured connection to the place.

The Amin family is one of the few Island-born dynasties that can trace their family history on the Island back several generations along the paternal and maternal lines.

Khaliesha Amin and her younger brother Khairin are both fifth-generation Christmas Island locals.

“You can’t name a lot of people that have been here that long,” Khairin Amin says.

The siblings can trace their family’s origins back to Maluku Islands and Boyan in Indonesia, which Khairin says is an easy way to tell how long a family has lived on the Island.

“You know your family has been here for generations when you are from one of those two places,” he explains.

Like most families that arrived early in the Island’s settlement, the Amin family moved here for the phosphate industry.

Khairin says the family was initially involved with the marine aspect of the mining operations but have branched out to other roles across the decades, including the siblings’ grandfather and father.

The mine drew the family in, but the Island itself and its many charms is what has kept the Amins here for so long.

The Island’s warm temperature, high rainfall, isolation from other land masses and geological features have enabled it to support unique plant life and a rich assortment of animals.

For the Amin siblings, the Island was also the perfect backdrop for an adventurous upbringing.

“Growing up as kids, we just knew nature,” says Khaliesha, who is currently working in the Environmental and Community division of the mine.

“The ocean was our front yard and the jungle was our back yard.”

Khairin says his parents and other community members gave the Island’s youth the know-how to thrive in this environment.

“They were a lookout for me” he recalls.

“When you climb that tree, make sure you don’t go too high; you can’t eat that fruit because it’s poisonous.

“It’s almost like you’re raised by the Island.”

After a certain point, Khaliesha, Khairin and their friends were trusted to venture out on their own and they took full advantage of what the Island had to offer.

“We learned to cut trees on our own at 9 or 10 years old so we would grab a machete and just walk around and explore,” Khairin says.

“We used to just go and find all these hidden trails in the back of the Kampong blocks.” Khaliesha adds: “No sitting in the house playing games – none of that.

“It was cops and robbers around the whole Kampong, running around and climbing trees.”

Nature alone isn’t the only aspect of the Island that makes it a special place to live and grow up.

Christmas Island has a diverse mix of cultures, with settlers and workers bringing cultural and religious traditions from several areas, with Australian, Chinese, Malay and European the biggest ethnic groups.

But with most of the small population concentrated around the main settlement of Flying Fish Cove, a closeness between the groups developed that has all but erased racial tension on the Island in the Amin siblings’ lifetime.

“Everywhere you go you can’t escape it, so what are you going to do, hate it?” Khairin explains.

Khaliesha adds: “The kids here, we all pretty much grew up like a close-knit family. It doesn’t matter what race you are, we’re all like brothers and sisters.”

Khaliesha says that inclusiveness applies to the various religious and cultural festivals that are celebrated on the Island, including Christmas, Easter, Chinese New Year and Hari Raya/Eid.

“It doesn’t matter what our cultural or religious background is, pretty much everyone is invited to everything,” she says.

“If it’s Christmas, you are sitting on Santa’s lap,” Khairin adds.

“I don’t care what race you are, you are getting the presents as well.”

Both siblings credit the approach taken by the Island’s school with helping to build a sense of inclusiveness.

“It was Christmas time and in music class we learned how to sing Merry Christmas in three different languages,” Khairin relates.

“I can remember to this day, you have to incorporate everyone – no one is missing out.”

Although the majority of the siblings’ schooling took place on Christmas Island, both were among the many residents who moved to the mainland to complete Year 11 and 12.

Though Khaliesha was actually born in Perth after a cyclone forced her mother to give birth off-Island, the high school stint was the first time she or her brother had ever lived there and it took some adjusting to.

“When we had to go to school in Perth, it was a bit of a shock,” she says.

“Not having the things that we’re used to doing on the Island, it is a bit of a loss for us.

“I don’t think we appreciated the Island enough before we went to Perth.”

After graduating, they returned to Christmas Island determined to stay, both have purchased their own homes and are now playing their parts in keeping their home’s culture and history alive.

“The elderly people will not be here forever and the younger generation needs to step up and take over to keep these traditions alive,” Khaliesha says.

Khaliesha is doing so by serving on Christmas Island Phosphates’ community development committee, where she helps determine how $200,000 each year in funding provided by the mine will be distributed.

“Every year there are two sponsorship openings and any sporting group, any educational group, pretty much anyone who wants to apply to have funds for any of their projects, items/equipment or celebrations are welcome to apply,” she explains.

“We consider how applications benefit the community as a whole and then we grant them funds and the majority of it is community events.”

Khaliesha believes cultural events would still proceed without funding from the mine, but for some, maybe on a smaller scale.

“It would depend on how much funding they get, because some community groups don’t have revenue or an income like companies,” she says.

Although Khairin isn’t directly involved in the broader community work, he is carrying on his own family’s tradition by working for the mine in the same role once held by his grandfather.

“I’ve just finished my second year as an electrical apprentice,” he says.

“My granddad worked as an electrician as well and there are a couple of old timers that I’m working with that used to work with him.”

The mine’s current lease expires in 2034 and the possibility of it closing for good has made Khairin reflect on what that would mean for his family and the Island more broadly.

“It was the mine that got us here through the generations,” he says.

“It started off with the mines and we are going to be the last ones on the mines.

“If you lose the mine, not only do you lose your livelihood, but you lose a part of yourself, a part of your history.”

The pair want the industry that eventually replaces mining to leverage all the aspects of the Island they love to succeed.

“The Island has a lot to offer with the culture and history we have here, with the native wildlife and marine life,” Khaliesha says.

“It’s all so beautiful.”

Khairin adds: “I hope it’s something that highlights how we grew up, how we think it is just the best thing ever.”

Neither Khaliesha nor Khairin wants to be forced off the Island because of lack of work, but the fate of the Island’s economy is even more important on a personal level for Khairin.

He has a three-year-old daughter, Zaakirah, and wants to make sure the sixth generation of the Amin family on Christmas Island is able to remain there.

“I knew when I had a family of my own, I wanted them to have the same experience growing up that I had,” he says.

“If the mine closes and we don’t have any other options, my daughter will have to look elsewhere.

“If there’s enough industries and opportunities here, Christmas Island can continue to be our home.”