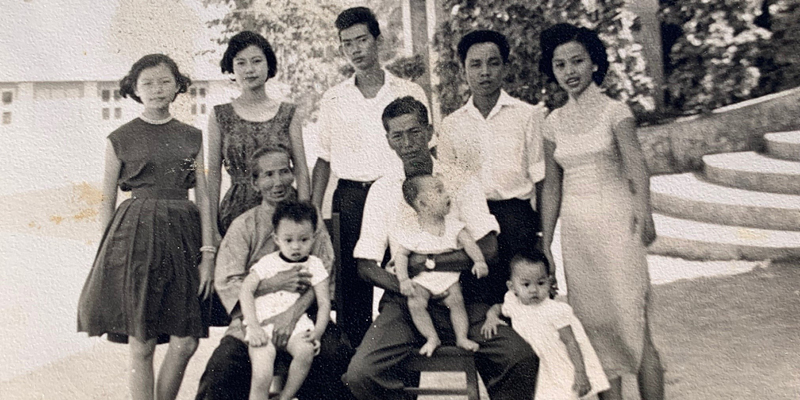

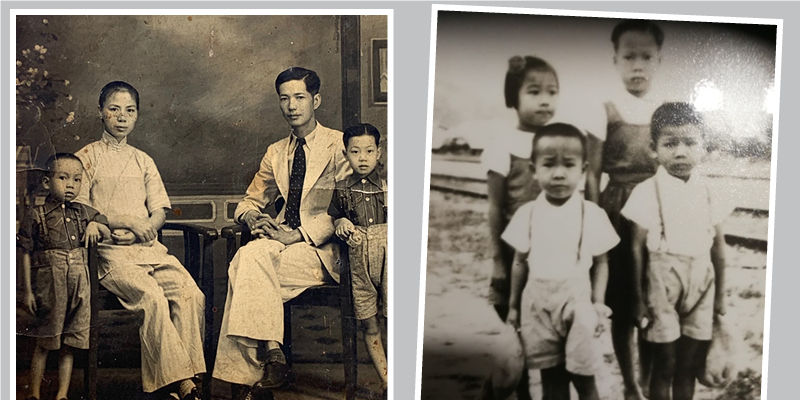

Tuang Kheng Meng and Wan Kan Ho

One of the most fascinating chapters in World War II happened not far from Australian shores on an Island that would one day become an Australian territory governed by the mainland.

The Battle of Christmas Island in 1942 and the subsequent occupation by Japanese armed soldiers only lasted until 1945, but that three-year span has had a lasting effect on the Island’s culture which is still felt today.

Both Wan Kan Ho and Tuang Kheng Meng or “Ken”, both 85 years of age now, were young boys living on the Island when the Japanese invaded, but their lives took very different paths as a result of the occupation.

Even before the Japanese arrived, Wan and Ken’s lives had marked differences.

Ken was born on Christmas Island and had lived there all his life with his father Tuang Ah Hew, and other family members.

In Wan’s case, he had felt the pain of war long before it reached Christmas Island’s shores.

Born in Canton, China, Wan lost his biological parents at a young age – his mother when he was only three years old. His father died of starvation a couple of years later, leaving Wan and his older brother to fend for themselves.

“I was three years old and my mother died already, I was just a boy,” Wan says. “Sometimes they say Mother’s Day on the radio and my tears come out.”

However, in pre-war Christmas Island, working men with technical qualifications and families in their homelands were rewarded for good work with houses and the opportunity to bring family members to live on Christmas Island.

Wan’s adopted father Wan Chong was a foreman and in 1941 he was permitted to retrieve Wan from China and bring him to Christmas Island.

He wouldn’t stay there for long.

Japan joined World War II in November 1941 and early the next year, Wan was one of the dependents of Island residents who evacuated the Island to Singapore on supply ship TSS Islander.

However, the tense situation in Singapore and other nearby ports forced the Islander back to Christmas Island with its passengers on board less than two months after it departed.

“We travelled along the Indonesian islands but there was no place to hide, so we went straight away to Christmas Island,” Wan says.

As Wan recalls, Japanese armed forces weren’t far behind.

“We live in the Island one day and the next day the Japanese arrived,” he says.

Ken remembers what the feeling was like on the Island in the lead-up to the arrival of the Japanese.

All the high-ranking British officers had evacuated with the exception of a captain and three British officers and a small number of Indian soldiers.

Christmas Island’s defences consisted primarily of a six-inch ex-naval gun and a few fortifications.

On the evening of March 10, a group of seven Indian soldiers led a munity and prepared to surrender to the Japanese.

“The Indians say, ‘how can we fight with them?’,” Ken explains.

“So, what happened, they killed the five British officers and threw them into the sea.

“When the Japanese arrived, they just put a white flag in up and surrendered.”

With roughly 1000 Japanese navy marines disembarking on to the Island, Ken and Wan were among the many Asian workers and their families who fled to the safety of the jungle.

“I followed my parent in the jungle and the Japanese know the people too scared, ask the people to come out,” Wan remembers.

“The Japanese sent leaflets into the jungle, saying, ‘Come, come, we will not do any harm to you.’,” Ken adds.

“There was no fight, no killing on the Island.”

Most Islanders returned from the jungle and life resumed under Japanese rule.

Both men say they were mostly treated well by the Japanese soldiers.

“The adult they don’t like because they can’t tame them, but they mostly like the boy,” Wan remembers.

“When I was a boy, every time I walked past the soldier they gave me a biscuit and lollies to eat, they wanted to win over the boys.”

Ken had a similar experience, but also remembers being disciplined for not bowing correctly – often accompanied by the phrase ‘bakayaro’, which means ‘stupid person’ in Japanese.

“If you bow not much or not too low, they would come and ‘bakayaro!’ and they give you a smack,” Ken says.

“We were just kids, what do we know? We don’t know anything.”

Both boys were also sent to the Japanese school that was set up in Flying Fish Cove, which was taught by young Japanese soldiers.

“As we are young, we just learn a, i, u, e, o and na, ni, nu, ne, no,” Ken says.

“Japanese is very simple one, same like English, you would learn words like dog or cat, very simple,” Wan adds.

However, in 1943 the two boys’ lives came to a fork in a road.

A ship filled with supplies was sunk by a British submarine, claiming the lives of three Malay workers and two Japanese men in the engine room.

Wan recounts people’s recollections of the event.

“The people didn’t know, they thought it was a big shark,” Wan says.

"But that’s not a shark, it’s a torpedo and it went ‘Boom!’ By the time the second one hit the ship was finished.”

Declaring a lack of food on the Island, the Japanese evacuated several hundred men – mostly bachelors – and families to its territory in Surabaya in Indonesia.

Ken and his family were sent to Surabaya – which he suspects was because he believed his father was a volunteer in the British army.

Wan nearly joined him but he says he was lucky to be able to remain behind on Christmas Island for the remainder of the Japanese occupation.

It normally took two days to sail to Surabaya on the ship, but Ken recalls there were so many British submarines around that it took a whole week.

“At night-time they switched off the light and went without light,” he says.

“But one night one of the Indian passengers at the back smoked a cigarette which was not allowed by the Japanese due to the presence of the British submarines.

“The Japanese caught him and the next morning they pulled him out and bend him over to whack him on the backside.

“All the families sitting there can see them whack the guy because he smoked at the back.”

When they did arrive at Surabaya, the Christmas Islanders were sent into a barracks, with the families on one side and the single men on the other.

There were two fences surrounding the compound, and Ken remembers seeing people from Malaysia being starved and dying as punishment for trying to clear the fence.

“When I was young, I could see them crawling there, dying down there,” Ken says.

The Islanders were all subject to water and food rationing, administered by the Indonesian and Sikh guards.

One day there was friction between the Islanders and the Indians and one of the Islanders was killed.

Fearing for his family, Ken’s father told everyone to close the doors and keep quiet, but they still caught the attention of the guards.

“I remember they keep banging on the door just to frighten us,” Ken recalls.

“Walking around and bang, bang, bang, bang.”

The Japanese were holding a meeting away from the camp at the time and Ken’s father met with the other Islander men to attempt to escape and get help from the Japanese.

“My father said, ‘We have to go to the headquarters and make a report or else they might come in and kill all of us’,” Ken explains.

Ken’s father and another young man were selected to reach the Japanese and, fortunately, the mission was successful.

“I remember we report to the Japanese, and the Japanese came back and they pick a few of the Sikh,” he says.

“I remember still looking at it. Ask them bend over, take off their trousers, and you know the Japanese are famous for the stick, and they gave a couple of whacks on the back side.

“That I remember, the whack.”

Ken and the other Islanders were transferred away from their tormentors until the Japanese surrendered and were overthrown by the Indonesian locals in 1945.

With the Japanese occupation over, Ken’s father moved into a big house in Surabaya with another family from Christmas Island.

Ken was in Indonesia for four or five years, and while there he learned to speak fluent Indonesian.

With the 300 or so Chinese bachelors from Christmas Island now free to live on Surabaya, many of them married Javanese women.

At the same time, the phosphate mine on Christmas Island was short of workers, so the mine’s new general manager John Rupert Paris sailed to Surabaya on the Islander to retrieve the men who had been taken there by the Japanese during the war.

Ken says his father played a key role in bringing people back to Christmas Island on the Islander.

In the aftermath of the war, Ken and Wan were both back on Christmas Island but were in the unfortunate position of having to transition back to English schooling.

Having been disrupted by the Japanese occupation and time spent in Indonesia, both boys were told they were too old to return to school.

Ken recalls that his father had to fill out paperwork with the district office to push him down a year group so he could be schooled again.

In Wan’s case, he was put down two years. However, neither was able to stay in school long and both took up apprenticeships.

“The teacher said you have to go out for work in apprenticeship, so I left,” Wan says.

“I worked for five and a half years before I was qualified.”

Like many Islanders throughout the settlement’s history, Wan earned a living at the phosphate mine, which was then operated by the British Phosphate Commission (BPC).

Wan eventually left Christmas Island because the way the BPC treated his father.

“My father had to go to Singapore for treatment, and after the treatment they wouldn’t let him back to the Island,” Wan explains.

“BPC treated us no good, you know. I worked so hard for the BPC and then my father goes and gets treatment, and they can’t let him back.

“So, I left the Island.”

Wan spent seven years working for Spicer International in Singapore before ending up in Australia.

When Ken left school, he couldn’t get a job and thought about moving to Singapore to join the police, but his father stopped him.

“I nearly went, but then my father said, “Oh we got a job in the office”. So, I started there. In the office. That’s how it started. Then I start my apprenticeship in the drawing office,” Ken says.

Ken’s father had been a long-time draftsman on Christmas Island and was tasked with recruiting workers from neighbouring regions.

Ken says he was so good at it that he was eventually banned from recruiting in Singapore because there was a skills shortage and Christmas Island was causing a ‘brain drain’ in Singapore.

Ken also left Christmas Island to make his own way, moving to Australia as well.

Both former Christmas Islanders discovered their training on the Island made them highly valued by the Australian employers.

Ken recalls that when a friend of his tried to show an employer his Australian certification the man asked for his Christmas Island papers instead.

“You know why? Because he trust the Christmas Island workers,” Ken says.

“All are very good workers. Real workers.”

The Japanese occupation remains a dark period in Christmas Island’s history, but it also made an important contribution to the culture that makes it such a special place to live today.

The Christmas Island bachelors who were taken to Surabaya brought their new wives and families back with them, injecting a new culture in the population and bringing the different groups of Asian labourers closer together.

“That’s why the Island had so many mixed children,” Ken says.

The women themselves also possessed a work ethic that matched or exceeded their husbands and helped the Island recover from the war.

“The Javanese ladies are all hard working,” Ken recalls.

“They are the one that work harder than the husband in Christmas Island.

They are the one who plant vegetables, drive jeep and sell these sort of things.

They are the hardest working ones.”

Today, Christmas Island enjoys a unique multicultural community where all the racial and ethnic communities mix together and live in harmony – it’s unclear how big a role the Japanese occupation played in this, but it certainly made an impact.