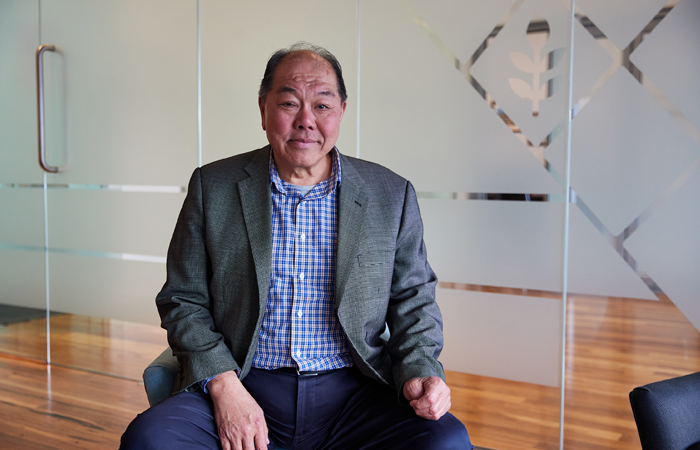

Lai Ah Hong

Lai Ah Hong started his Christmas Island journey sleeping on a wooden bed frame, with no mattress, in a three-square-metre army barracks style accommodation.

“I must say, it was a little bit different from what we expected,” Lai says.

“I was disappointed there was no mattress, they didn’t provide one and I couldn’t afford to buy one. Sleeping was horrible, the lack of sleep also affected our work performance.”

Lai’s unit, like many of the Malaysian and Singaporean single workers, was segregated from where the Caucasians lived and had no hot water to shower or bathe in.

That was in 1978 and Lai was just 23 – thrown into a society were Asian labour was exploited and authorities practiced a form of apartheid and segregation.

Lai had moved to the Island from Malaysia, to work for the phosphate mine as a labourer.

“When you come in, you get put in a floating gang, it's like, we were moved around working all over the place, and they’d say ‘ok now we want you to clean this or chop down this bush or move something,” he says.

Forty-two years later at 65, Lai is now based in Perth as the managing director of that very same mine, albeit a much bigger company.

He has come a long way from a time of abhorrent and unjust working and social conditions, but remarkably can look back and laugh at the hard times, including an incident when he and his colleagues were told to get off the coastal bus which was reserved for Caucasians and their families.

“The coastal bus, we did not know was just for the Caucasians and their families, I remember there were about four or five of us, we just jumped on it because we were not in work clothes as we were training up to be train guards and it was raining,” he says.

“By the time we jumped on they asked who we were and we said we were train guards. The bus driver said, ‘You are not allowed to come on the bus. You guys should get off before we all get in trouble.’ I said, ‘we are not going to go anywhere, a bus is a bus.’”

It was a brave move considering many lived with the threat of ‘never to return’ (NTR) being stamped on official documents, which stopped workers from returning to the Island if they had left on leave or to visit family, and was designed to deter troublemakers or people who stood up for their basic human rights.

Lai, however, was destined for leadership. Despite starting his mining career as a humble labourer, it didn’t take him long to fight for what was right.

With his mattress complaints going unheard, he and his friend thought they would try their luck at the local union office.

“We complained to the mine and we got nothing basically, and then while walking home one day we passed the union office. We told them we couldn’t work, because we couldn’t sleep so they noted our concern,” says Lai.

“One month later a mattress arrived, we didn’t even know it was coming, it just got dropped off in the room, as if it fell from the sky.

“I don’t think the we had that win on our own, I think the union had done a lot of groundwork before we made a complaint.”

It’s no surprise Lai then joined the Union of Christmas Island Workers, which was set up in 1975 and became an integral part of shaping the Island into what it is today.

“I was being pushed to join the union executive, only six weeks after I arrived on Christmas Island and ultimately became president of the union,” he says.

“At that time there were about 1800 workers, so you can imagine it was quite a big workforce.”

In those early days Lai only planned to stay on the Island for three years to make some money to be able to go home to marry his now wife and raise a family, but his plans changed when a man named Gordon Bennett became secretary of the union.

Lai says Mr Bennett is lauded as a hero on the Island, having helped to change guest-worker status for Asian employees so they could become permanent residents.

“Through the union we achieved an increase to $30 a week and wage parity, which was a big deal back then and working conditions started to improve over the next two years,” Lai says.

By 1982, Lai wanted to bring his wife over to the Island, but still couldn’t access appropriate accommodation and Asian workers were not allowed to buy property. To get around this he invested in his own business.

“I got a tender for a general store shop, which had two bedrooms attached, so that solved my problem, so my wife could come over,” he says.

By 1987, the Australian Government, which operated the mine, claimed it was not financially viable and shut it down.

“When the mine was closed, suddenly we all had a very uncertain future. The key question was, what do we want to do? Without a job a lot of people decided to leave,” Lai says.

“But many chose to stay. Now, if you were to ask people to stay for a month or two or three, I think that was still quite reasonable, but when you ask people to stay without a job and with no income, it was a big ask. It was not easy to motivate people to stay and fight to reopen the mine.”

Lai, alongside Gordon Bennett, believed in the Island and its people, and in a story of true community spirit they began a movement to reopen the mine.

“We rallied the Island’s workers to band together to raise the money to reopen the mine,” he says.

Along with Gordon Bennett, Lai was an essential figure in investing and leading the Island’s community to reopen the mine.

“I was the first one to put in $100,000 into the shareholder trust to encourage others. Over just three days [MR1] we raised $3.5 million to reopen the mine,” Lai says.

“I believed we would get there in the end and we convinced the people. Immediately everybody chipped in, $5,000 here, $10,000 there, some $100,000.

“Even with the money raised it still took us nearly three years, including getting knocked back twice by the government through the tender process. Ultimately, we took the government to court and we won, forcing them to reopen the tender process, after which we were successful.”

Lai says that although the movement was successful in reopening the mine in 1991, it wasn’t easy to manage worker expectations who also thought they had a say in the business as shareholders.

“Let me put it this way. You never satisfy everybody, but we didn't do it just for profit, we mainly did it for jobs, and we could only employ 30 people at a time through job sharing, despite having 200 shareholders,” he says.

Sadly, Gordon Bennett tragically passed away in the same year the mine was reopened, but Lai carried on as one of the founding directors to lead it to success.

“Those days the bureaucrats never believed we would be able to run the business. We worked very hard to make it financially viable. Each year we would make small money and return some money to the shareholders and after 1994 things started to improve” Lai says.

“We started to see profits in the millions and that is when we started to reinvest. Mainly all back into the ageing infrastructure, the Island’s people, the school, and cultural and community events.”

Lai admits he doesn’t have a crystal ball to tell the future of what the Island will become.

“The first mining lease was for only 10 years and no one in their wildest dreams could have imagined we would still be going after 30 years. Since 1990, we have exported over 15 million tonnes of phosphate, created hundreds of jobs on Christmas Island and paid hundreds of millions in taxes, royalties and dividends,” he says.

“We have created a successful diversified business with interests in mining, agriculture, energy, maintenance, transport and logistics, and are now looking at tourism and infrastructure investments.

“If we can keep the mine going for another 14 years, that would be great. It will assist us to grow and diversify further so we can create a future for the next generation of Christmas Islanders.”

Lai believes a closure of the mine would be detrimental to the community without an alternative industry.

“To maintain the Island’s population and lifestyle, the Commonwealth would need to subsidise the community which would cost tens of millions of dollars a year,” he says.

Phosphate Resources Limited and its subsidiaries are currently the largest employer on the Island, creating more than 400 direct and indirect jobs.

“We're not only providing jobs, but we're providing services and infrastructure, and I cannot imagine how the Island would survive if the mine was to be closed tomorrow,” Lai says.

The PRL group also runs Indian Ocean Oil Company, which supplies fuel for the Island and CI Maintenance Services, which provides asset management and maintenance services for the detention centre and Indian Ocean Stevedores, which provide pilotage and shipping services.

It has also very recently purchased a ship, the Red Titan, to carry phosphate and provide a shipping service to the community in an aim to drive down the cost of living for residents.

Lai says as part of the company’s mining lease it pays a levy, which amounts to over $30 million since it started, for conservation, including the rehabilitation of land that has important environmental value.

“There is a misconception that a modest expansion of mining will have a significant impact on the environment, but the greatest threat to the environment is feral and invasive species, and we’ve contributed a lot of funding over the years to combat this,” he says.

Looking ahead to the future, Phosphate Resources Limited wants to play a central role in transitioning Christmas Island to a more diversified and sustainable economy.

“We are already looking into opportunities in tourism and infrastructure and whatever else comes our way,” says Lai.

Since the days of sleeping without a mattress Lai has never stopped working to ensure the future of Christmas Island and its community.

“We want to continue to create opportunities for the younger generation and future generations of Christmas Islanders, so they can live, work and bring up their families in the place we call home,” he says.