Ma ChoyChan

For Ma ChoyChan, her connection to Christmas Island is built on hard work.

Although she was born on Christmas Island in 1957, she owes her upbringing on the paradisical island to her father Ma Yat’s work ethic and determination.

Born in GuangZhou, China, Ma Yat lost his first wife to starvation in the famines that followed the Japanese invasion of the Chinese mainland in the Second World War.

Desperate for work, Ma Yat ventured to Vietnam and then Hong Kong, which had reverted to British rule after the Japanese occupation ended.

While in Hong Kong, Ma Yat was contracted by the British and sailed to Nauru and Ocean Island to work as a labourer.

Armed with only a Chinese-English dictionary, Ma Yat taught himself broken English.

But the language barrier didn’t stop Ma Yat from catching the eye of an Australian engineer by the name of Roy Neville.

For two weeks, unbeknownst to Ma Yat, Mr Neville watched him closely.

In this time, he observed Ma Yat’s work ethic, diligence and honesty.

When Mr Neville was transferred from Nauru to Christmas Island to serve as Island Manager, he was so impressed with Ma Yat that he brought him with him.

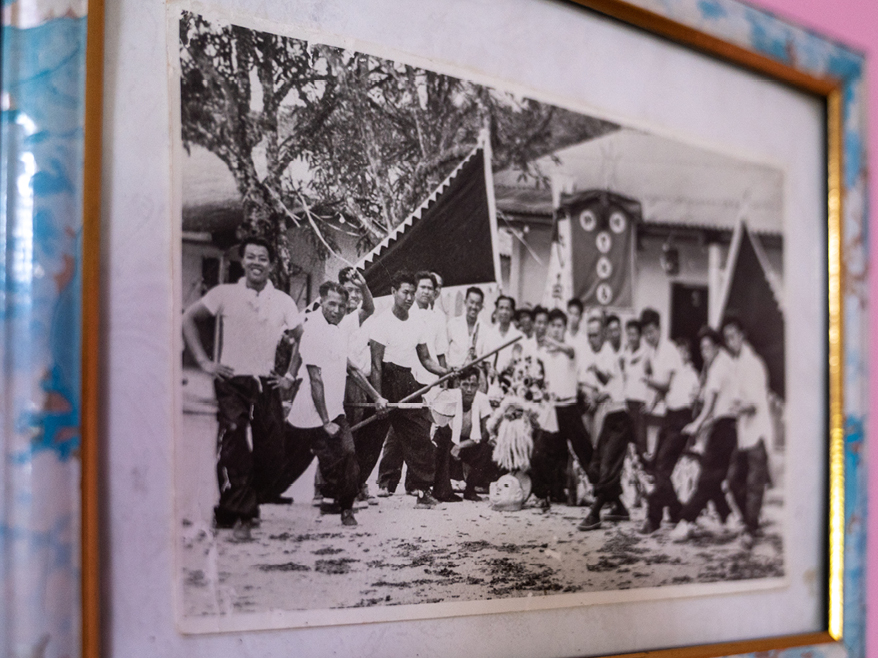

After arriving on Christmas Island in the late 1940s, Ma Yat was awarded the title of Chief Butler.

With Mr Neville responsible for the production of phosphate for the British Phosphate Commission (BPC), being his butler was a position of trust for Ma Yat.

Now settled on Christmas Island, Ma Yat was introduced to a widowed woman in China through letters.

This woman was ChoyChan’s mother and the pair were married at a simple traditional ceremony after she arrived from China with her daughter.

Ma Yat and his wife had two daughters before ChoyChan was born.

The contracts for Island Managers were only five years long, so Mr Neville and his family left the island when she was still a toddler.

The bond between the Neville and Ma families was more than professional, and ChoyChan remembers meeting the Nevilles when she was nine years old when Mrs Neville got a relief contract on Christmas Island.

The Neville family took ChoyChan’s family to dinner at the local Chinese restaurant, and the families kept in correspondence into the 1980s.

The opportunity Mr Neville had given Ma Yat proved equally resilient, and he retained his position as Chief Butler for several of Mr Neville’s successors.

ChoyChan has fond memories of those days on Christmas Island, which had an abundance of wildlife, a booming mining industry and a friendly mixture of Chinese and Malay residents.

“It was a tropical paradise, there was lots of jungle to explore, beaches, safety, security and helpful, friendly residents,” she recalls.

“The island had no natural predators, so it was quite safe for children playing around.

“Christmas Island moulded us to be honest, contented and caring people.”

But just as work brought the Ma family to Christmas Island, it would also force them to leave.

When Ma Yat reached 57, British Phosphate Commission policy required him to retire and leave the island, even though her mother was four years younger and still working part time.

“Retirees were considered no longer productive, and likely to be a liability, with advancing age, she remembers. “Batches of workers, including my father had to vacate the island. They were sad departures for hundreds of families, and even the single over aged workers had to leave.”

From the freedom of Christmas Island, ChoyChan moved to Singapore, where the family could only afford to live in a house with four other families.

When she was old enough, ChoyChan wanted to pick a job that would let her support her parents.

She says there were not many career options for women in the 1970s.

“There were maybe four choices: secretary or office girl, cleaner, teacher, and nurse,” she explains.

“As a secretary, I was not pretty enough. As a cleaner, those were all taken by hard-working girls. As a teacher, I was clever enough.”

That left nursing as her best option.

In 1975, ChoyChan’s application to work on Christmas Island was accepted by Dr Stephenson and BPC, leaving her parents behind in Singapore because they were non-residents and non-citizens of Australia, which had assumed sovereignty at that stage.

She was only 18, and with no previous experience she was thrown into the thick of the action at Christmas Island Hospital, the Adult Dental Clinic and the School Dental Clinic.

“You didn’t need a qualification, because it was run by BPC they could set their own policies and I was just training on the job,” ChoyChan says.

“My second sister was still working for the government at the administrator’s house, and I had friends there.

“There was lot’s to learn, but it was a stable job and it was pleasant enough.”

At the same time, the population on Christmas Island was spiking as more Asian workers were allowed to bring wives to the island.

“It was really meant for single workers, but I think BPC felt sorry for the young men in their 20s and 30s,” she says.

“Of course, when you have wives, what do you get? You get children.

“And when you have children, what do you need? The hospital and then schooling and teachers.”

ChoyChan worked at the hospital while hundreds of children were born each year.

But then the mining work started to dry up and ChoyChan saw the same pattern that affected her father’s generation with workers started to get pushed off the island.

At 26, ChoyChan took action to make sure she could still send money to her parents in Singapore.

Having been born in Christmas Island, she was a citizen of Australia and was allowed to move to the mainland.

Away from the more relaxed standards of Christmas Island, ChoyChan had to finish her high school education and get a formal nursing qualification to continue her career.

Picking up shifts as a dental assistant, she worked, studied and supported her parents, who she had been able to bring to Australia to live with her.

“It was hard work having to look after my parents and study,” she says.

But through the trademark Ma work ethic, she had graduated in Perth in 1990 and could resume her career as a nurse.

Now 64, she has been working as a nurse since, long past the age her father was forced into retirement.

Far from slowing down, ChoyChan is still actively seeking out work, even in remote places.

In 2019, she had the opportunity to return to Christmas Island as a nurse on a temporary contract for two weeks.

It was the first time she had been to her birthplace in decades.

“It was very nice to be back there,” she says.

“Everything looks smaller, of course, but because I was born there and have an attachment, everything meant a lot to me.”

Another opportunity came in August 2021, this time for two months.

ChoyChan tried to find a permanent position on Christmas Island, but was unsuccessful.

With travel expenses so high, she can’t afford to fly there on her own and doesn’t know when she’ll be able to return next.

But in the family tradition, she hopes hard work will see her through.